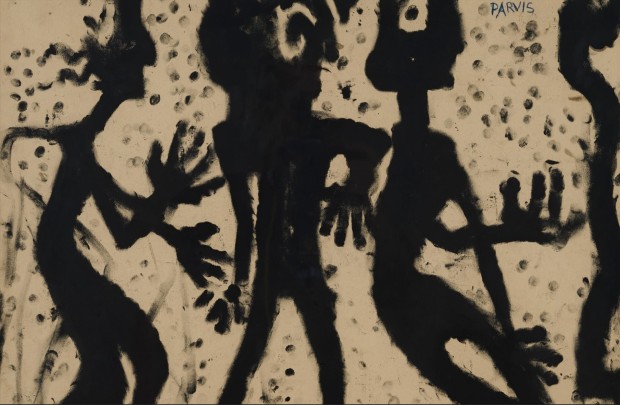

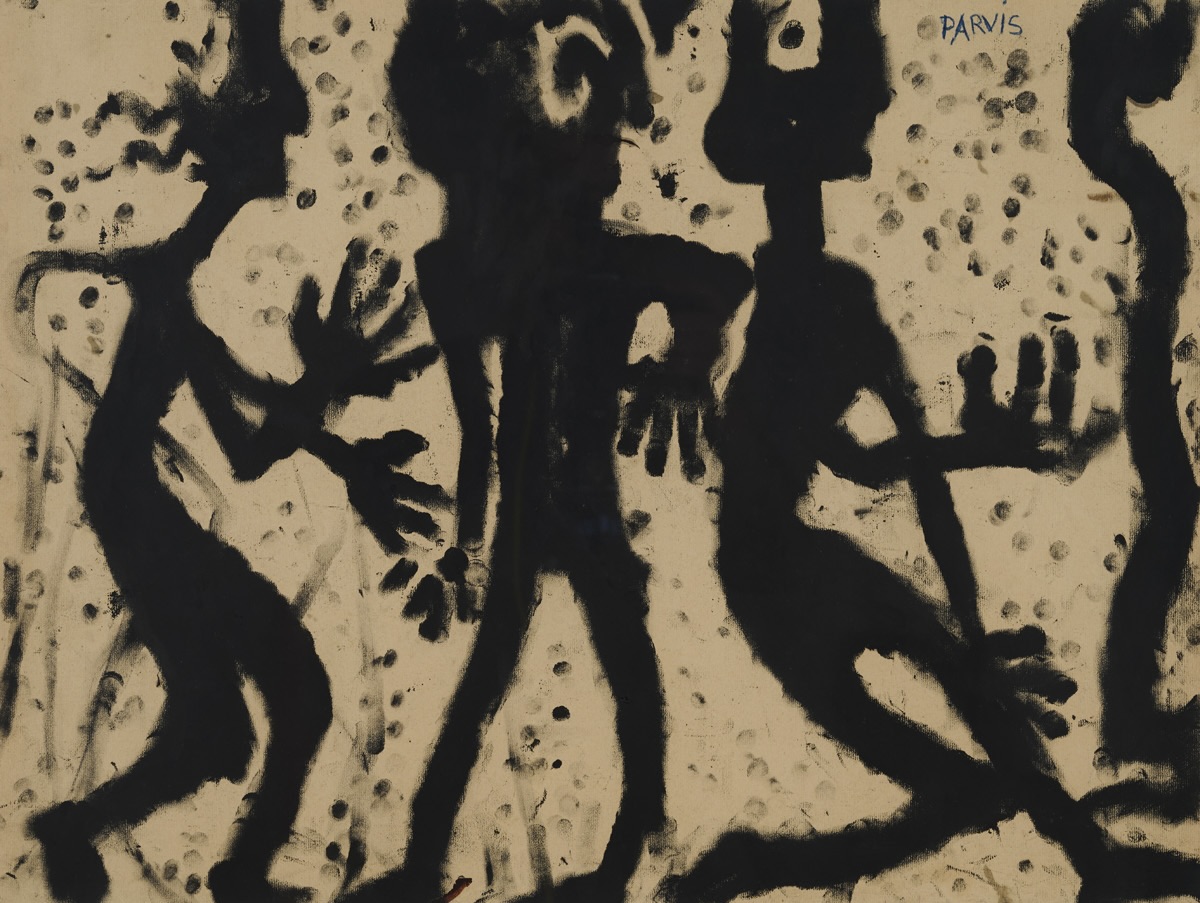

Parvis, 1937. Chinese ink (finger-applied) on paper. 44 × 57.8 cm. €300,000 / €400,000

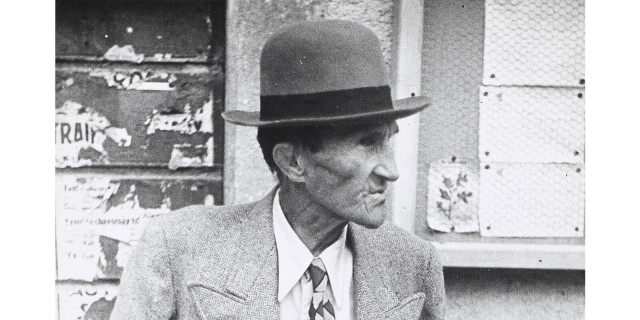

At the start of his adult life, everything seemed to be going well for Louis Soutter. Born into a well-to-do Swiss bourgeois family and cousin of the architect Le Corbusier, he first turned to painting, studying in the Paris studios of Jean-Paul Laurens and Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant. He was also a gifted violinist, trained by Belgian composer Eugène Ysaÿe—admired by Debussy, Fauré, and Saint-Saëns. At 26, Soutter married an American heiress, Madge Fursman, who was also a violinist. The couple moved to the U.S., where Soutter was appointed head of the Fine Arts Department at Colorado College—a promising transatlantic future seemingly within reach.

But a deep depression cut that path short. Soutter returned to Switzerland, resumed his career as a musician, and developed a reputation for eccentric behavior—he once reportedly walked out of an orchestra performance mid-concert. His fading eyesight and flamboyant style alarmed his family, who eventually had him institutionalized in a home for the elderly in Ballaigues. He experienced the confinement as a harsh social exile—but turned fully to drawing and painting as a form of survival.

Admired by both Le Corbusier and Jean Giono, Soutter’s work took a radical turn in his sixties. Suffering from severe arthritis in his fingers, he abandoned pen and pencil and began applying ink directly with his finger—a method he called toucher au doigt. As art historian Michel Thévoz observed, “what might have been experienced as a disability became, in his case, the catalyst for a complete reinvention of visual language.” Using his finger as a living brush and shifting movement to the elbow, Soutter intensified his physical engagement with the work. His drawings became stark, expressive compositions of black and white, aimed at what Thévoz calls “pure sign-making.”

Now represented by Galerie Karsten Greve, Soutter’s late works are considered among the most pioneering of the 20th century.