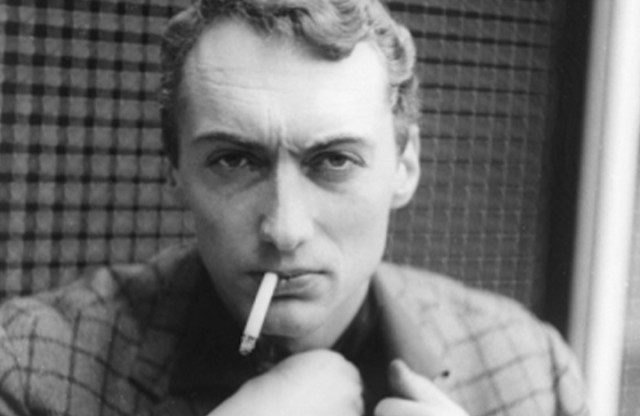

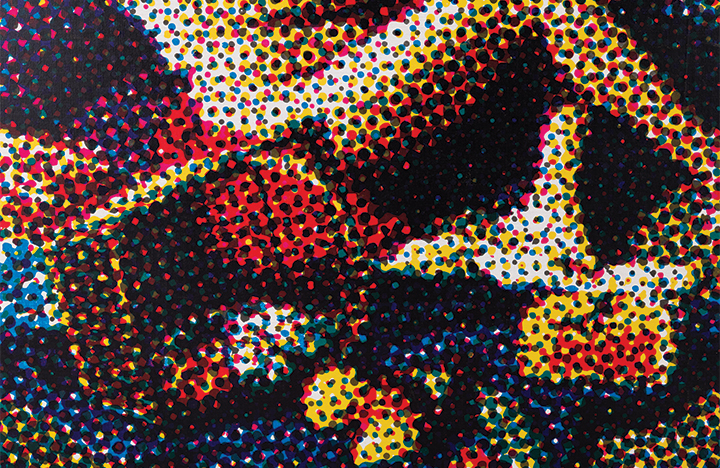

For the critic Pierre Restany—reclining at the right of the composition created in 1964 by Alain Jacquet—Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (est. €50,000–70,000) is above all an artistic gesture that far exceeds the notion of a European response to American Pop Art. For this work, the artist uses the serigraphic “Ben-Day dots” process, which revolutionized the world of advertising. While the technique had long benefited American comic-book illustrators—Girls’ Romances (DC Comics), drawn by Tony Abruzzo and later reworked into Roy Lichtenstein’s famous M-maybe series, remaining one of the best-known examples—it enables Alain Jacquet to create a mise en abyme that reinterprets Western painting.

By revisiting Édouard Manet’s painting exhibited a hundred years earlier at the 1864 Salon des Refusés, he appropriates not only the painter’s work but also the Renaissance art that Manet himself was questioning. The transgressive aspect that had provoked scandal in the nineteenth century—the normalization of female nudity—shifts here into a context of impending sexual liberation: nudity is no longer transgressive; rather, it is the logic of serial reproduction that is perceived as an infamous attack on classical art.

Yet by defining Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe as the founding act of Mec’Art, Restany, with a touch of humor, is not mistaken. Technically, Mechanical Art can be understood as a humanist version of Pop Art, or even as a distant, relaxed cousin of Op Art, but it also exposes the asymmetry of the male gaze upon woman—a “guy’s gaze,” a male gaze whose societal implications are particularly resonant today.

Finally, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe paves the way for the postmodern mechanics of interpretative reappropriation and quotation, which would come to define much of the contemporary art field, and sets the first steps on a path later explored by artists such as Richard Prince and Jeff Koons.