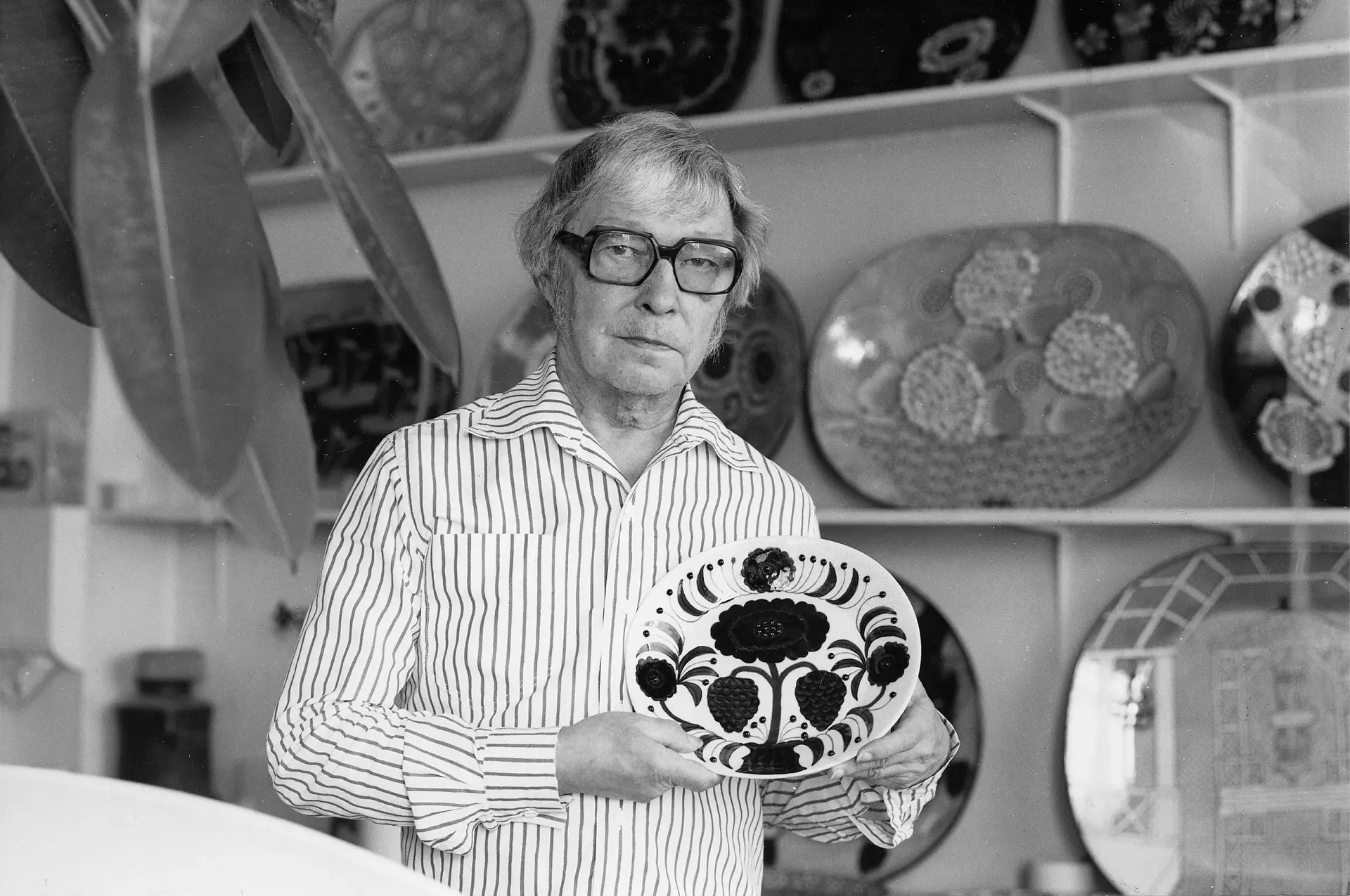

Birger Kaipiainen occupies a unique, almost separate place in the history of Scandinavian design. Far from the refined functionalism that made Finnish post-war style famous, he chose the path of nature, dreams and ornamentation. His ceramics evoke Art Nouveau revisited with a poetic, almost baroque touch.

Birger Kaipiainen studied at the Helsinki School of Applied Arts before joining the Finnish porcelain manufacturer Arabia in 1937, a veritable laboratory of Finnish design. He remained loyal to the company for more than fifty years, creating a unique body of work at the crossroads of art and decoration. In the 1950s, when modernism dominated all fields of creation, he invented a deeply personal language featuring organic shapes, deep blue enamelled surfaces, pearl inlays, and stylised fruits and flowers, as if taken from a northern dream.

Imagination versus convention

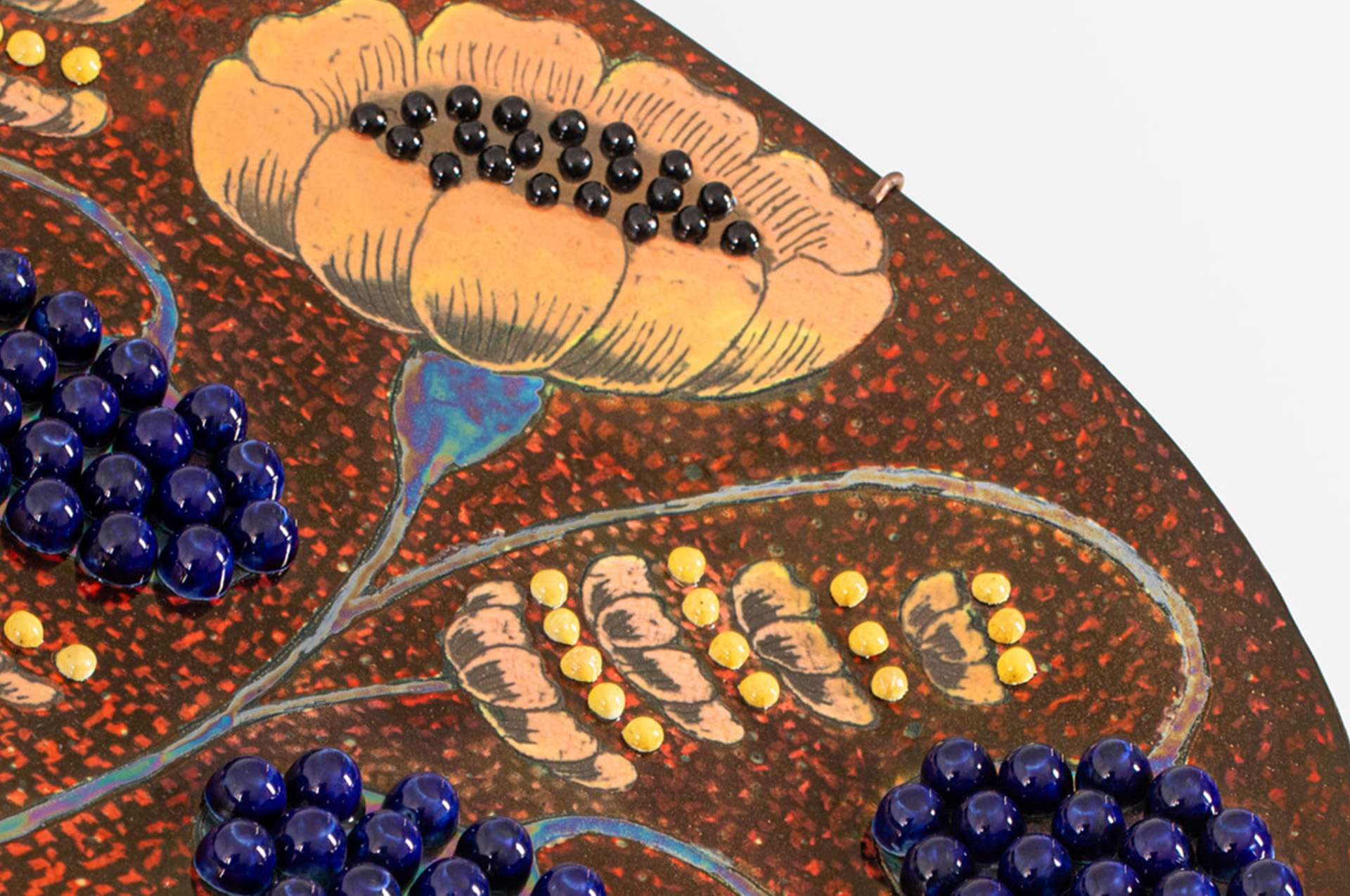

At Kaipiainen, dishes and wall panels are covered with motifs of birds, flowers, clusters and mysterious fruits, evoking both Byzantine icons and Venetian mosaics.

In contrast to modernist austerity, he championed an unapologetically ornamental style, inspired by the Italian Renaissance he adored. For Arabia, he produced everyday objects – including the famous The Paratiisi (Paradise) tableware set created in 1960 – as well as sculptures often adorned with pearls, which became his signature.

The three dishes presented in the sale, estimated at €5,000/7,000 and €8,000/12,000, perfectly illustrate the artist's stylistic choices. They encapsulate the essence of Kaipiainen's style: an almost melodic, delicate composition, undoubtedly evident for this lover of Chopin's Nocturnes. The deep tones, often dominated by cobalt blue and black, are enriched with golden details, as if the northern light were reflected in fragments.

Thirty-seven years after his death, Birger Kaipiainen still fascinates with the depth of his work. Beneath the refinement of the enamels, we sense a form of poetic resistance that perhaps challenges modernity. His ceramics, fragile and timeless, remind us that ornamentation is, after all, perhaps not a crime.